When PhD Supervision Goes Wrong: Handling Difficult Supervisors

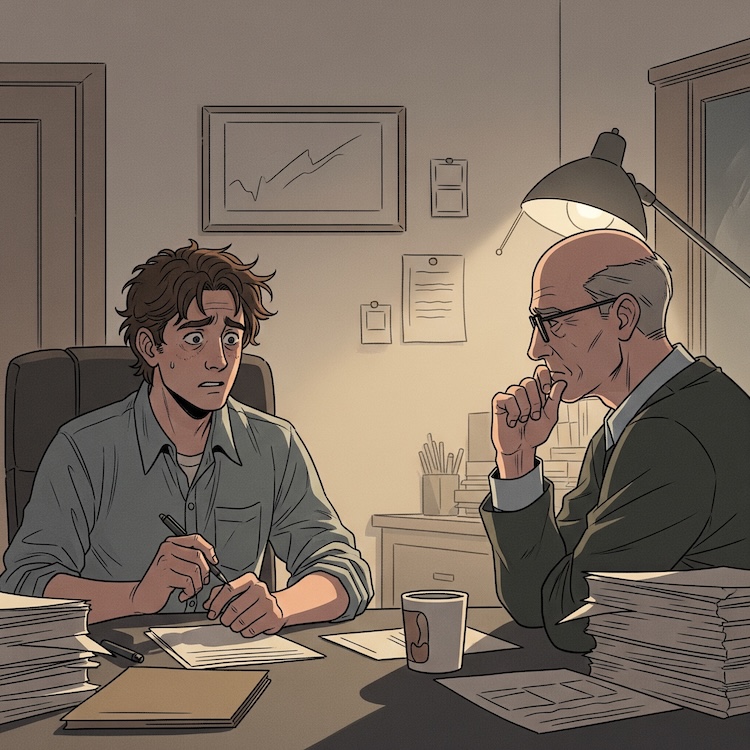

The doctoral journey is a transformative period, marked by intense intellectual engagement, personal growth, and the pursuit of original research. Central to this experience is the relationship between the PhD student and their supervisor. This guide aims to provide PhD students with a comprehensive understanding of how to identify, comprehend, and navigate challenging or problematic relationships with their supervisors, offering strategies for resolution and self-preservation.

Significance of the Supervisor-PhD Student Relationship

The supervisor-PhD student relationship is one of the most critical components of a successful and fulfilling doctoral experience. The supervisor often acts as a mentor, guide, critic, and advocate, profoundly influencing the student's research direction, skill development, integration into the academic community, and future career prospects. As highlighted by Gorup and Laufer (2020), the supervisor is commonly "the central and most powerful person" in a doctoral student's academic life. Similarly, research discussed on EGU Blogs (2021) underscores this relationship as a "main variable contributing to PhD success." While many of these relationships are positive and nurturing, a significant number can become problematic, resulting in detrimental effects on both the student's academic progress and overall well-being.

This article will delve into the characteristics of ideal versus problematic supervisory dynamics, equipping students to recognise red flags. It will explore the multifaceted causes of such issues, from individual factors to systemic institutional pressures, and examine their wide-ranging impacts. Crucially, it will outline strategic approaches for addressing these problems, offering actionable steps for communication, mediation, and, if necessary, formal escalation. Emphasis will also be placed on managing the outcomes of such interventions and prioritising self-care. Finally, the article will consider the crucial role institutions play in fostering healthy supervisory environments and preventing such problems from arising or escalating.

Understanding the Landscape: The Ideal vs. Problematic PhD Supervisory Dynamic

The Ideal Supervisory Relationship

An ideal supervisory relationship serves as the bedrock for a PhD student's academic and professional development. It is typically characterised by several key attributes. Regular, constructive feedback is essential, providing students with clear, actionable insights into their work. Clear guidance on research direction, methodology, and academic standards helps students navigate the complexities of their projects. Mutual respect forms the foundation, fostering an environment where ideas can be exchanged openly and critically without fear of personal judgment or bias. While providing support, an effective supervisor also encourages the student's independence, empowering them to take ownership of their research and develop into autonomous scholars. Beyond academic guidance, a strong supervisor often acts as a mentor, offering advice on career development, networking, and navigating the broader academic landscape. This supportive dynamic aims to challenge the student intellectually while fostering their confidence and resilience. Understanding these positive attributes is crucial for students to recognise when a relationship begins to deviate significantly into problematic territory.

Prevalence and Silence Surrounding Problematic Relationships

Problematic supervisor-PhD student relationships are, unfortunately, not a rare occurrence within academia. Despite their impact, these issues are often shrouded in silence. The inherent power imbalance, where students are in a "subordinate and dependent position socially, intellectually, and financially" (Gorup and Laufer, 2020), often discourages students from speaking out due to fear of repercussions. Statistics reveal the extent of the problem: Gorup and Laufer (2020) note that around 50% of doctoral researchers discontinue their doctorates, with supervisory issues being a contributing factor. Furthermore, a global survey by Nature, also referenced by Gorup and Laufer, found that European doctoral researchers frequently list "impact of poor supervisor relationship" as a top concern. The same survey indicated that 21% of respondents had experienced bullying, with a staggering 48% identifying their supervisors as the most frequent perpetrators. This data underscores that problematic supervision is a systemic issue rather than isolated incidents, validating the concerns of students who find themselves in such difficult situations.

Recognising the Red Flags: Identifying a Problematic Supervisory Relationship

Understanding the signs of a deteriorating or inherently flawed supervisory relationship is the first step towards addressing it. These indicators can range from subtle communication breakdowns to overt misconduct, all of which can hinder a student's progress and well-being.

Common Indicators of a Problematic Relationship

1. Communication Deficiencies

Effective communication is the lifeblood of a healthy supervisory relationship. Deficiencies in this area are often early warnings. This can manifest as a chronic lack of regular meetings, making it difficult for students to receive timely guidance or discuss progress. Consistently ignored emails or requests for feedback leave students feeling adrift and undervalued. When feedback is provided, it might be infrequent, unhelpfully vague, or, conversely, overly harsh and demoralising, rather than constructive. PhD Academy (2022) highlights a lack of contact and harsh feedback as common problems. Furthermore, unclear or constantly shifting expectations and advice from the supervisor, as noted by Tress Academic (2023), can lead to confusion, wasted effort, and a sense of being perpetually unable to meet demands.

2. Mismatched or Ineffective Supervisory Styles

Supervisory styles vary, but certain approaches can become problematic if misaligned with student needs or inherently ineffective. Micromanagement, for instance, can stifle a student's developing independence and critical thinking, making them feel untrusted or overly controlled. Conversely, an "absentee" or disengaged supervisor provides little to no guidance, leaving the student to navigate the complexities of doctoral research alone. Tress Academic (2023) describes supervisors whose focus is on project results for their own benefit, rather than the student's PhD completion, which can sometimes lead to the excessive delegation of tasks unrelated to the student's core research. Another issue can be a supervisor's lack of subject matter expertise in a critical area of the student's research, especially if this was an expectation. These stylistic mismatches can lead to frustration and impede progress, as highlighted by discussions on supervisor control over projects (Gorup & Laufer, 2020).

3. Unprofessional, Unethical, or Abusive Conduct

This category encompasses the most serious red flags. Exploitation can occur when supervisors take undue credit for a student's work or ideas. Bullying or harassment, whether verbal, emotional, or psychological, creates a toxic environment. Tress Academic (2023) explicitly lists behaviours such as shouting, fits of rage, and bullying, including personal attacks based on performance, race, background, or gender. Discrimination based on any protected characteristic is unethical and illegal. Gorup and Laufer (2020) report that supervisors are identified as frequent perpetrators of bullying in surveys. Such conduct is unacceptable and can have severe and lasting negative impacts on students.

4. Negative Impact on Research Progress

A direct consequence of problematic supervision is often stalled academic progress. This can manifest as a project that languishes due to a lack of clear guidance, delayed or unhelpful feedback on drafts, or an inability to resolve methodological challenges. Supervisors who frequently impose radical changes in research direction without clear justification can derail a student's work, as noted by Gorup and Laufer (2020) regarding supervisor control over project topics and processes. Inadequate support for acquiring necessary skills, accessing resources, or navigating institutional hurdles further compounds these issues, leading to frustration and a feeling that the PhD is an insurmountable task.

5. Detrimental Impact on Personal Well-being

The personal toll of a problematic supervisory relationship can be immense. Students often experience increased stress, anxiety, and even depression as a direct result of the negative dynamics. A study by Kambouri et al. (2024) found that uncertain supervisory styles, characterised by indecisiveness and ambiguity, were linked with higher scores in depression, anxiety, and stress among UK doctoral students. Constant criticism, lack of support, or an abusive environment can lead to a significant loss of motivation, a diminished sense of self-confidence, and pervasive feelings of inadequacy or isolation. The EGU Blogs (2021) also highlight that the supervisor relationship can be a primary cause of mental ill health. Over time, these pressures can contribute to burnout, a state of emotional, physical, and mental exhaustion.

Self-Assessment: Questions to Reflect On

Before taking action, it's crucial for students to undertake a thorough self-assessment to clarify the nature and severity of the problems. This reflection can help in formulating a targeted approach. Consider the following questions:

- Duration and Persistence: How long has this pattern of behaviour been an issue? Is it an isolated incident, a recent development, or a persistent problem?

- Specific Impact: What is the concrete impact on my research progress (e.g., missed deadlines, unwritten chapters, rejected papers)? How is it affecting my mental, emotional, and physical health (e.g., sleep patterns, anxiety levels, motivation)?

- My Role and Attempts: Have I inadvertently contributed to any misunderstandings or communication breakdowns? What steps have I already taken to try and address the situation (e.g., direct conversation, seeking informal advice)? What were the outcomes?

- Desired Outcome: What is my ideal resolution for this relationship and my PhD? Am I looking for improved communication, clearer guidance, a change in specific behaviours, or something more fundamental?

- Tolerance Levels: What aspects of the current situation am I willing to tolerate, and what are my non-negotiables? At what point does the cost to my well-being or progress outweigh the benefits of continuing under the current supervision?

- Nature of the Problem: Does the situation feel primarily like a mismatch in expectations or communication styles, poor management, or does it cross into more serious territory like neglect, exploitation, or abuse?

Answering these questions honestly can provide clarity and focus, informing the next steps you might take.

C. The Importance of Systematic Documentation

Systematic documentation is a crucial tool for navigating a problematic supervisory relationship, particularly when the issues are persistent or severe.

Why Document:

- Objective Record: It creates a factual, chronological record of events, interactions, and communications, moving beyond subjective feelings or vague recollections.

- Pattern Identification: Reviewing documented incidents can help identify recurring patterns of problematic behaviour, which might be less obvious on a day-to-day basis.

- Evidence for Formal Steps: Should you need to escalate the issue formally (e.g., file a grievance, request a change of supervisor), documented evidence is invaluable and often required by institutional procedures.

- Clarity and Focus: The act of writing down specific incidents can help clarify your thoughts, understand the impact of the behaviour, and prepare you for discussions.

What to Document:

- Dates, Times, and Locations: For every specific incident, meeting, or significant interaction.

- Specific Behaviours/Quotes: Record factual descriptions of what was said or done. Use direct quotes where possible. Avoid emotional language or interpretations; stick to observable facts. (e.g., "Supervisor stated, 'This work is pathetic'" rather than "Supervisor was mean").

- Communications: Keep copies of relevant emails, text messages, or any other written correspondence. Note attempts to communicate that went unanswered.

- Impact: Briefly note the impact of the incident on your work (e.g., "Could not proceed with Experiment X due to lack of feedback on proposal Y") and your well-being (e.g., "Felt highly anxious after the meeting, unable to focus for the rest of the day").

- Witnesses: If anyone else was present and observed the incident, note their name(s).

How to Document Effectively:

- Contemporaneous Notes: Document incidents as soon as possible after they occur, while details are still fresh in your mind. Date every entry.

- Factual and Objective: Strive for neutrality in your descriptions. Focus on facts, actions, and direct statements.

- Secure Storage: Store your documentation in a secure, private location (e.g., a password-protected personal file or a dedicated notebook kept off-campus). Do not use university systems if you have concerns about privacy or access.

- Consistency: Try to be consistent in the level of detail you record for similar types of incidents.

This disciplined approach to documentation can empower you with a clear and credible account of your experiences, which is essential for reflection, communication, and potential formal action.

Unpacking the Roots: Why Do Supervisory Relationships Become Problematic?

Understanding the underlying causes of problematic supervisory relationships is crucial for students to move beyond merely reacting to symptoms and towards developing informed, strategic responses. These issues rarely stem from a single source but are often a complex interplay of supervisor-centric factors, student-related aspects, relational dynamics, and broader systemic or institutional pressures. Acknowledging this complexity can help in depersonalising the conflict and identifying more effective avenues for intervention.

Supervisor-Centric Factors

Several factors related to the supervisor can contribute to a challenging dynamic. A significant issue is the lack of formal supervisory training or experience. Many academics become supervisors based on their research prowess rather than proven pedagogical or managerial skills. As discussed in a study on supervisor competence in medical fields (Rie et al., 2017), there is a recognised need for supervisors to develop their competence, as this role has historically been learned through experience rather than formal training. This can lead to inconsistencies in supervisory quality.

Overwhelming workloads and institutional pressures also play a critical role. Supervisors are often juggling teaching, administrative duties, their own research, grant applications, and the need to publish. These pressures, highlighted by studies on institutional demands in doctoral programs (Vrinda et al., 2024), can lead to students having insufficient time, resulting in neglect, impatience, or superficial engagement. Personality traits of the supervisor can also be a factor; for example, an authoritarian style may clash with a student seeking collaborative guidance, while insecurity in a supervisor might manifest as defensiveness or unwillingness to admit gaps in their knowledge. Furthermore, poor management or communication skills, or an unclear understanding of their own supervisory role and responsibilities, can lead to ambiguous expectations, inadequate feedback, and a general failure to provide the necessary support and structure for the PhD student.

Student-Related Factors (and perceptions)

It's essential to consider factors related to the student, not to assign blame, but to understand the complete dynamic and identify areas where student agency can be fostered. Mismatched expectations are common: a student might anticipate a high degree of hands-on guidance, while the supervisor practices a more laissez-faire approach, leading to feelings of neglect. Conversely, a supervisor's attempts at close guidance might be perceived as micromanagement by a student seeking more autonomy. Difficulties in effectively communicating needs, progress, or boundaries can also contribute; students may feel intimidated or unsure how to articulate their concerns or requirements, leading to misunderstandings. A passive approach, where the student waits for direction rather than proactively seeking guidance or managing upwards, can exacerbate issues with a supervisor who is busy or less engaged. Cultural differences in communication styles, academic norms, or perceptions of hierarchy can also lead to friction if not acknowledged and navigated carefully by both parties. Recognising these aspects can empower students to adjust their communication strategies or seek clarification on expectations.

Interactional and Relational Dynamics

The relationship itself—the "space between" supervisor and student—can be a source of problems. A poor initial alignment of expectations regarding meeting frequency, feedback turnaround, research direction, or working styles can set a negative trajectory from the start. If these misalignments are not addressed, communication can deteriorate over time, leading to frustration and resentment on both sides. Minor, unresolved conflicts or misunderstandings can escalate, poisoning the overall atmosphere. Differing academic values (e.g., emphasis on theoretical innovation vs. practical application) or research philosophies can also create tension, particularly if the supervisor is not open to the student's perspective or if these differences weren't explored before commencing the PhD. The very nature of the PhD, a long-term, high-stakes endeavour, can put immense pressure on this dyadic relationship, making it vulnerable to breakdowns if not actively managed with mutual respect and open dialogue.

Systemic and Institutional Factors

Beyond individual and relational aspects, systemic and institutional factors play a profound role in why supervisory relationships become problematic. These often create an environment where negative dynamics can fester or go unaddressed.

- Power Imbalance: Perhaps the most significant systemic factor is the inherent power disparity. As Gorup and Laufer (2020) extensively argue, PhD students are in a "subordinate and dependent position socially, intellectually, and financially." This makes it incredibly difficult for students to challenge their supervisors or report issues without fear of negative repercussions for their studies, funding, or future career.

- Lack of Oversight and Accountability: Many institutions lack robust mechanisms for monitoring the quality of supervision or for effectively addressing student complaints. Gorup and Laufer (2020) note that universities are often perceived as "reluctant to address supervision-related problems," and academics may tend to blame students rather than the program or institution.

- "Publish or Perish" Culture: The intense pressure on academics to publish research and secure grants can inadvertently deprioritise supervisory duties. This pressure can trickle down, with supervisors pushing students for quick results, sometimes at the expense of thorough research or the student's well-being, or neglecting students who are not perceived as contributing directly to the supervisor's own research output.

- Inadequate Institutional Support Structures: The absence of readily accessible and trusted mediation services, insufficient or non-mandatory training for supervisors in mentorship and management (EGU Blogs, 2021), and unclear or intimidating grievance pathways contribute significantly. Students may not know where to turn or may find existing channels unhelpful.

- Normalisation of a "Tough" PhD Experience: Some academic cultures inadvertently perpetuate the idea that the PhD is an inherently gruelling trial by fire. Gorup and Laufer (2020) mention that the doctorate is often "fashioned as a trial, a time of enormous hardship, of which only the fittest survive." This mindset can lead to the tolerance or even encouragement of overly harsh, neglectful, or demanding supervisory practices, as they are seen as part of the "weeding out" process.

These systemic issues demonstrate that problematic supervision is not merely about "a few bad apples" but is often symptomatic of deeper structural failings within academia that require institutional-level attention and reform.

Key Points: Roots of Problematic Supervision

- Supervisor-centric factors: Lack of training, workload pressures, challenging personality traits, and poor management skills.

- Student-related factors: Mismatched expectations, communication difficulties, passive approach (awareness helps agency, not blame).

- Interactional dynamics: Poor initial alignment, escalating unresolved conflicts, differing academic values.

- Systemic/Institutional factors: Critical role of power imbalances, lack of accountability, "publish or perish" culture, inadequate support structures, and normalisation of harsh PhD environments. Addressing these requires institutional reform.

The Ripple Effect: Impact of Problematic Relationships

Problematic supervisor-PhD student relationships are not benign; they cast long shadows, affecting students' mental and emotional health, their academic journey, and even their future professional lives. Understanding these impacts is vital for appreciating the seriousness of the issue.

On Student Well-being

The psychological toll of a dysfunctional supervisory relationship can be severe and is increasingly well-documented. Students in these situations frequently report heightened levels of stress, anxiety, and depressive symptoms. A key study by Kambouri et al. (2024), surveying UK doctoral students, found that "a large proportion of participants fell in the severe and extremely severe categories in the depression, anxiety, and stress sub-scales," and that supervisory styles significantly predicted these mental health outcomes. Specifically, "higher scores in the uncertain supervisory style...were linked with higher scores in depression, anxiety, and stress." Continuous negative interactions, lack of support, or an abusive environment can lead to a significant erosion of self-esteem and confidence. Students may begin to doubt their abilities, feel isolated, and lose their passion for research. Prolonged exposure to such stressors can contribute to burnout, characterised by emotional exhaustion, cynicism, and a reduced sense of personal accomplishment. In the most severe cases, these experiences can have lasting psychological impacts, requiring significant time and support to overcome.

On Academic Progress and Outcomes

The academic consequences of poor supervision are often tangible and detrimental. Delays in project completion are common, as students struggle with unclear guidance, inadequate feedback, or a lack of necessary support. The quality of the research itself may suffer if students are not effectively mentored in research design, critical analysis, or writing. According to a study from Tanzania, problematic academic performance includes being dissatisfied with the journey, making unsatisfactory progress, exceeding timelines, and considering quitting. This aligns with broader findings where reduced publication output is another potential outcome. Perhaps most critically, problematic supervisory relationships are a significant contributing factor to the attrition of PhD students. Gorup and Laufer (2020) highlight that supervisory issues often contribute to a doctoral student's decision to discontinue their PhD, contributing to the alarming statistic that around 50% of doctoral researchers do not complete their doctorates. A longitudinal study in Belgium also found that supervisor support is negatively related to dropout (Glorieux et al., 2024).

On Future Career Trajectories

The negative impacts can extend beyond the PhD itself, affecting future career trajectories. A strained or abusive relationship may result in poor or non-existent letters of recommendation, which are crucial for academic and many non-academic positions. The student's professional network may be damaged if the supervisor is their primary link to the broader research community. Furthermore, a deeply negative PhD experience can understandably lead to a disillusionment with academia, causing talented individuals to leave the field altogether. Even for those who complete their PhDs, the stress and lack of mentorship might mean they are less prepared or confident in transitioning to their post-PhD careers, whether in academia or industry.

Strategic Navigation: Preparing for and Taking Action

Once a problematic supervisory relationship is identified, students need to prepare strategically before taking action. This involves understanding the available support systems, clarifying personal goals for resolution, and considering various approaches.

Understanding Available Support Systems and University Resources

Most universities offer a range of support systems, although their visibility and accessibility can vary. Students must familiarise themselves with these potential avenues for advice and intervention.

Departmental Contacts:

Within your own department, key figures can often provide initial, informal advice or mediation. These may include:

- Head of Department (HoD) / Chair: The HoD is responsible for the overall functioning of the department, including postgraduate affairs. They may be able to offer guidance or intervene informally if the situation warrants it.

- Graduate Coordinator/ Director of Graduate Studies: This individual often has specific responsibility for postgraduate students and may be the primary point of contact for issues related to supervision or academic progress.

- Departmental Postgraduate Tutor/Advisor: Some departments have a dedicated academic staff member who serves as a general advisor for PhD students, in addition to their direct supervisors.

These individuals can often clarify departmental policies, offer a neutral perspective, or facilitate communication between the student and supervisor.

University-Level Services:

Beyond the department, universities typically provide centralised support services:

- Ombudsperson's Office: An Ombudsperson (or similar role) offers confidential, impartial, and informal advice and assistance in resolving conflicts or navigating university procedures. As described by Simon Fraser University's Ombudsperson Office, their role can help identify conflict situations and routes to resolution. They do not typically take sides but can help explore options and facilitate mediation.

- Student Counselling Services: These services provide confidential mental health support, which is vital when dealing with the stress and emotional toll of a problematic relationship.

- Graduate Student Association/Union: Student unions often provide advocacy services, advice on rights and procedures, and peer support networks.

- Dean of Graduate Studies Office / Graduate School: This office oversees graduate education university-wide and may have specific staff or procedures for handling supervisory disputes or academic appeals. The University of Toronto's School of Graduate Studies provides guidelines outlining whom students can talk to (SGS, UofT).

Reviewing Relevant University Policies:

Knowledge is power. Students should proactively locate and read relevant university policies, typically found on the university's website or student portal. Key documents include:

- Student Grievance Policy / Complaints Procedure: Outlines the formal steps for lodging a complaint.

- Code of Conduct for Supervisors / Staff: Defines expected standards of professional behavior.

- Dignity and Respect / Anti-Harassment & Anti-Bullying Policies: Detail procedures for addressing such misconduct.

- Specific Policies on PhD Supervision / Graduate Research Handbooks: These often outline roles, responsibilities, and expectations for both students and supervisors. Examples like the conflict resolution codes from University College Dublin illustrate the types of frameworks that may exist.

Understanding these policies empowers students by clarifying their rights, the expected standards, and the official channels available for seeking resolution.

Clarifying Your Goals and Realistic Outcomes

Before initiating any action, it's essential to reflect on what a "resolution" would ideally look like for you, while also being realistic about potential outcomes. Possible goals might include:

- Improved Communication: More regular, constructive meetings and timely, helpful feedback from the current supervisor.

- Mediated Agreement: Resolving specific conflicts (e.g., about research direction, authorship, or working style) through a facilitated discussion and agreeing on a clear path forward.

- Behavioural Change: A formal or informal intervention leading to the cessation of unprofessional, unethical, or abusive conduct by the supervisor.

- Change of Supervisor: In cases where the relationship is deemed irretrievably broken or harmful, securing a new supervisor might be the primary goal. This is often considered a last resort.

- Clearer Boundaries: Establishing and having respected boundaries around workload, communication times, or personal space.

Acknowledging that not all desired outcomes are always achievable is also important. The goal is to work towards the best possible resolution within the given constraints and available options, prioritising your well-being and academic progress.

Overview of Strategic Approaches

Depending on the nature and severity of the problem and your personal goals, different strategic approaches may be appropriate. The following table provides a comparative overview:

| Strategic Approach | Description | When to Consider | Potential First Step |

|---|---|---|---|

| Direct, Assertive Communication | Addressing concerns directly with the supervisor in a calm, constructive, and non-accusatory manner, focusing on specific behaviours and desired changes. | Mild to moderate issues; situations where misunderstandings might be a factor; an underlying relationship that has some positives; the student feels relatively safe to speak up. | Carefully prepare specific examples of problematic behaviours and their impact. Articulate desired changes clearly. Request a dedicated meeting to discuss your progress and working relationship. (Science.org, 2008; PhD Academy, 2022) |

| Informal Mediation / Third-Party Assistance | Involving a neutral and trusted third party (e.g., Head of Department, Graduate Coordinator, Ombudsperson) to facilitate discussion, help clarify issues, and guide towards a resolution. | Direct communication has failed, is too intimidating, or is unlikely to be productive; complex interpersonal issues require an objective perspective to break a deadlock. | Consult with the chosen third party (e.g., Graduate Coordinator, Ombudsperson) to explain the situation and seek their advice on how they might assist. (SFU Ombudsperson) |

| Formal Escalation (Grievance / Change of Supervisor) | Utilising official university channels (e.g., grievance procedures, formal request for change of supervision) to report serious issues or seek a fundamental change in the supervisory arrangement. | Serious misconduct (bullying, harassment, discrimination, exploitation); persistent neglect or abuse; irreparable breakdown of the relationship; failure of all informal methods to resolve critical issues impacting well-being or progress. | Thoroughly review the university's formal grievance policy and/or procedures for changing supervisors. Gather all systematic documentation. Seek advice from the student union or Ombudsperson on navigating the formal process. (UCD Policies; PhD Academy, 2022) |

Choosing the right strategy, or combination of strategies, depends heavily on a careful assessment of the specific situation, the institutional context, and your personal comfort levels and goals.

Taking Action: Implementing Strategies

Once a strategic approach is chosen, careful implementation is key. This section details actionable steps for each of the primary strategies: direct communication, informal mediation, and formal escalation.

Strategy 1: Direct, Assertive Communication with Your Supervisor

Addressing issues directly with a supervisor can be daunting, but is often the most effective first step for mild to moderate problems or misunderstandings.

1. Preparation Steps:

- Define Specific Issues & Desired Changes: Be concrete. Instead of "You're never available," try "I've found it challenging to get timely feedback on my last two chapter drafts, which has delayed my progress. I would appreciate it if we could agree on a timeframe for feedback, perhaps within two weeks of submission." Gosling & Noordam (2008) for Science.org emphasise preparing an agenda and specific questions.

- Prepare Talking Points with "I" statements: focus on your experiences and needs. For example, "I feel concerned when research directions change frequently without discussion, as it makes it difficult for me to plan my work effectively. I need more clarity and collaborative decision-making on major project shifts."

- Anticipate Reactions: Consider how your supervisor might respond and prepare brief, calm replies to potential defensiveness or disagreement.

- Choose an Appropriate Time and Request a Meeting: Email your supervisor to request a meeting specifically to discuss your progress and working relationship. Avoid ambushing them or trying to discuss serious issues in passing. (See Appendix for template email).

2. During the Conversation:

- Stay Calm and Professional: Maintain a respectful tone, even if the conversation becomes difficult. Avoid accusatory language.

- Focus on Specific Behaviours and Impact: Refer to your prepared examples. Explain clearly how specific behaviours affect your work and well-being. Stick to facts rather than interpretations of their intent.

- Listen Actively: Give your supervisor a chance to explain their perspective. Acknowledge their points, even if you don't agree with them. The goal is a dialogue, not a monologue.

- Clearly State Needs and Desired Changes: Reiterate the specific changes you are seeking (e.g., regular weekly meetings, clearer feedback criteria, a more defined project scope).

- Seek Agreement on Actionable Steps: Collaboratively identify solutions or next steps. For instance, "Could we try scheduling a 30-minute check-in every Friday morning?"

3. Follow-up Actions:

- Summarise in Writing: Send a polite email after the meeting, thanking them for their time and summarising the key discussion points, any agreements made, and action items for both of you. This creates a record and reinforces understanding. (See Appendix for template email).

- Schedule a Follow-up (if appropriate): If specific changes were agreed upon, consider scheduling a brief check-in meeting in a few weeks to review progress.

- Monitor the Situation: Observe if the agreed-upon changes are implemented and if the situation improves. Continue documenting.

Strategy 2: Seeking Informal Mediation or Third-Party Help

If direct communication is unsuccessful, too intimidating, or inappropriate for the severity of the issue, involving a neutral third party can be beneficial.

Identifying a Suitable Mediator/Facilitator:

Consider individuals who are respected, neutral, and have some understanding of departmental/university dynamics:

- Head of Department / Graduate Coordinator: Often a good first port of call as they have a vested interest in student success and departmental harmony.

- A Trusted Senior Academic: If there's a senior faculty member respected by both you and your supervisor, they might be willing to facilitate informally.

- University Ombudsperson: Specifically trained in conflict resolution and can offer impartial advice and formal or informal mediation services. Their confidentiality can be a significant advantage.

Discuss the pros and cons of each. For instance, a departmental figure is familiar with the context but may not be perceived as entirely neutral by all parties. An Ombudsperson offers neutrality and expertise but may be less familiar with specific departmental intricacies.

The Mediation Process Explained:

- Initiating the Request: Approach the chosen third party, explain the situation concisely and factually (your documentation will be helpful in this regard), and inquire if they can assist in facilitating a discussion or mediating.

- Preparation: Clearly outline your concerns, the impact on you, and your desired outcomes for the mediation. Be prepared to share your perspective calmly and listen to your supervisor’s.

- During mediation, the mediator's role is not to take sides or impose a solution, but to help both parties communicate effectively, understand each other's perspectives, and collaboratively find a mutually agreeable way forward. Focus on issues, not personalities. Be open to compromise.

- Outcome: The aim is a documented agreement on specific actions or changes. If no agreement is reached, the mediator may suggest other avenues or help you understand your options. Even without full agreement, the process can clarify misunderstandings.

Strategy 3: Formal Escalation (Grievance or Changing Supervisor)

Formal routes are typically a last resort, undertaken when informal methods have failed or when the issues are particularly severe.

1. When to Consider Formal Routes:

- Persistent failure of direct communication and informal mediation to resolve significant issues seriously impacting your PhD.

- Clear instances of serious misconduct such as bullying, harassment, discrimination, research misconduct (e.g., plagiarism of student work), or abuse.

- Situations where the supervisory relationship is irretrievably broken, making continued progress under the current supervisor impossible or severely detrimental to your well-being.

- Clear violation of university policies or codes of conduct by the supervisor.

2. Filing a Formal Grievance:

- Understand the Procedure: Locate and meticulously read your university's official student grievance policy. This document is paramount. University College Dublin's Code of Practice for Conflict Resolution provides an example of such detailed procedures.

- Compile Documentation: Gather all your systematic documentation (logs, emails, meeting notes, witness accounts if any). This evidence is crucial.

- Follow Submission Steps: Adhere strictly to the outlined procedure for submitting the formal complaint, including any specific forms, deadlines, and designated offices.

- Process Expectations: Be prepared for a potentially lengthy process. The university will typically investigate the complaint, which may involve interviews with you, the supervisor, and any relevant third parties. Understand the possible outcomes, which can range from dismissal of the complaint to recommendations for mediation, disciplinary action against the supervisor, or facilitation of a change in supervision.

3. Process for Requesting a Change of Supervisor:

PhD Academy (2022) suggests changing the supervisor as an option when problems are severe and unresolved. This is a significant step with several considerations:

- Key Considerations:

- Impact on Research: How much will your project need to change? Can your existing work be salvaged? What are the implications for your timeline and funding?

- Availability of Alternatives: Are there other faculty members with the appropriate expertise and willingness to take you on?

- Departmental/University Procedures: What is the official process for requesting a change? This varies widely.

- Potential Repercussions: While institutions should protect students, there can be informal fallout. Consider how the university might mitigate this.

- Procedural Steps:

- Discreet Exploration (if appropriate and permitted): Depending on policies and your comfort level, you may discreetly sound out potential alternative supervisors about their capacity and interest. This needs to be handled delicately.

- Consult Key Figures: Discuss your intention with the Head of Department, Graduate Coordinator, or Ombudsperson. They can advise on the feasibility and process.

- Formal Request: Submit a formal written request as per university procedures. This request should clearly, calmly, and factually state the reasons for the request, focusing on the irreconcilable differences or harm caused by the current supervisory relationship and its impact on your PhD progress and well-being. Avoid using emotive language; let your documented evidence speak for itself.

Formal escalation is a serious step and should be undertaken with careful preparation and a clear understanding of the potential processes and outcomes. Seeking advice from student support services or a student union representative throughout this process is highly recommended.

Aftermath and Self-Preservation: Managing Outcomes and Prioritising Well-being

Regardless of the strategy pursued and its outcome, the period following an attempt to resolve supervisory issues can be a challenging one. It's crucial to evaluate the results, decide on further steps if needed, and, most importantly, prioritise self-care and well-being.

Evaluating the Results of Your Actions

After taking steps to address the problematic relationship, it's important to objectively assess whether the situation has improved. Consider the following:

- Tangible Changes: Have the specific problematic behaviours changed? For example, are meetings now regular and constructive? Is feedback timely and helpful? Are expectations clearer?

- Impact on Research: Is your research progressing more smoothly? Are you feeling more motivated and engaged with your work?

- Impact on Well-being: Do you feel less stressed, anxious, or demoralised concerning your supervision? Has your overall sense of well-being improved?

- Adherence to Agreements: If mediation or a formal process resulted in an agreement, is your supervisor (and are you) adhering to its terms?

If the situation has not improved sufficiently, or if it has worsened, you may need to:

- Revisit Your Strategy: If you initially took an informal approach, consider whether a more formal strategy is now necessary.

- Seek Further Advice: Consult with trusted advisors (Ombudsperson, Graduate Coordinator, Student Union) again to discuss next steps.

- Consider an Exit Strategy: In some intractable situations, if all reasonable avenues have been exhausted and the environment remains detrimental, focusing on completing the PhD as efficiently as possible (if feasible) or, in extreme cases, exploring options such as transferring or discontinuing, might become necessary considerations, though these are major decisions requiring careful thought and consultation.

Ongoing assessment allows for adaptability and informed decision-making as the situation evolves.

Essential Self-Care Strategies During Difficult Times

Navigating a problematic supervisory relationship is emotionally and mentally draining. Prioritising self-care is not a luxury but a necessity for resilience and well-being.

1. Stress Management Techniques:

Actively engage in practices that help mitigate stress. These can include:

- Mindfulness and Meditation: Even short daily practices can help reduce anxiety and improve focus.

- Regular Physical Activity: Exercise is a powerful stress reliever. Find an activity you enjoy and make time for it.

- Hobbies and Interests: Engage in activities outside of your PhD that bring you joy and relaxation.

- Adequate Sleep and Nutrition: Prioritise consistent sleep schedules and healthy eating habits, as these significantly impact mood and energy levels.

- As Manousos Klados (2023) advises, "Taking care of your well-being is not a luxury; it’s an essential ingredient for resilience and success on your PhD journey."

2. Building and Utilising a Support Network:

Isolation can exacerbate the negative effects of a difficult supervisory relationship. Lean on your support systems:

- Peer Support: Connect with other PhD students. They can offer understanding, empathy, and shared experiences. Departmental or university-wide PhD student groups can be invaluable.

- Friends and Family: Talk to trusted friends and family members about what you're going through (while respecting confidentiality where necessary).

- University Counselling Services: Professional counsellors can provide a confidential space to discuss your feelings, develop coping strategies, and manage stress. (Students should search their university's internal website for "student counselling" or "mental health support").

- External Mentors: If possible, cultivate relationships with mentors outside of your direct supervisory line who can offer an objective perspective and career advice.

3. Maintaining Perspective and Focus:

It can be easy for a problematic supervisory relationship to overshadow everything else. Try to maintain perspective:

- Separate the Issue from Your Worth: Remind yourself that supervisory problems are often not a reflection of your capability or the value of your research.

- Focus on Achievable Goals: Break down your research into smaller, manageable tasks. Celebrate small victories to maintain motivation.

- Recall Your Motivations: Reconnect with why you decided to pursue a PhD in the first place. This can help sustain your focus during challenging times.

- Compartmentalise (where possible): Try to limit the extent to which the supervisory issue bleeds into other areas of your life. Set aside specific times to address it, rather than letting it consume all your thoughts.

Vigilant self-care and a strong support system are crucial for navigating these challenges and emerging with your well-being intact.

Systemic Change: The Role of Institutions in Fostering Healthy Supervisory Environments

While individual students can and should take steps to navigate problematic supervisory relationships, the ultimate responsibility for fostering healthy and supportive research environments lies with academic institutions. Systemic changes are necessary to prevent such issues from arising and to ensure fair and effective resolution mechanisms when they do.

A. Mandatory and Effective Supervisor Training

Institutions must invest in comprehensive, mandatory, and ongoing training for all academic staff involved in PhD supervision. As highlighted by McKenna and Motshoane (2023) for Times Higher Education, effective training should be delivered by credible experts, take context seriously, be an ongoing endeavour, and focus on developmental practices rather than mere compliance. This training should cover:

- Best practices in mentorship, guidance, and feedback.

- Effective communication and interpersonal skills.

- Conflict resolution strategies.

- Recognising and appropriately responding to student distress and mental health challenges.

- Understanding and promoting diversity, equity, and inclusion in supervision.

- Awareness of power dynamics and ethical responsibilities.

A study by Rie et al. (2017) also emphasised that PhD supervisors themselves report a need and desire for competence enhancement programs. Proactive and continuous professional development for supervisors is a cornerstone of preventative institutional action.

B. Clear, Accessible, and Fair Policies and Procedures

Universities have a duty to establish and maintain transparent, easily navigable, and fair policies and procedures related to PhD supervision. This includes:

- Clear PhD Supervision Standards: Defining the roles, responsibilities, and expectations for both students and supervisors.

- Conflict Resolution Pathways: Multiple, clearly defined pathways for resolving disputes, ranging from informal departmental intervention to formal mediation. Examples like the University College Dublin's Code of Practice illustrate comprehensive frameworks.

- Formal Grievance Procedures: Robust and impartial processes for students to file formal complaints about supervision, ensuring due process for all parties.

- Procedures for Changing Supervisors: A clear, supportive, and non-punitive process for students who need to change supervisors due to irresolvable issues.

- Protection from Retaliation: Strong safeguards to protect students from any form of academic, professional, or personal retaliation for raising concerns or filing complaints.

These policies should be readily accessible to all students and staff, for example, through graduate school handbooks and university websites, as seen in the guidelines provided by the School of Graduate Studies at the University of Toronto.

C. Robust and Confidential Support Structures

Beyond policies, institutions must provide well-resourced and genuinely confidential support structures where students can seek advice and assistance without fear:

- Ombudsperson Offices: Independent, impartial, and confidential offices that can provide information, explore options, facilitate communication, and offer mediation services.

- Confidential Counselling Services: Accessible mental health support tailored to the unique pressures faced by PhD students.

- Dedicated Graduate School Support Staff: Trained personnel within the Graduate School or equivalent body who can advise students on policies, procedures, and available resources for addressing supervisory issues.

- Anonymous Reporting Channels: Mechanisms for students to anonymously report concerns about supervision quality or problematic conduct, which can help institutions identify patterns and systemic problems.

The effectiveness of these structures hinges on their confidentiality, accessibility, and the trust students place in them.

D. Promoting a Culture of Respect, Accountability, and Mentorship

Ultimately, preventing problematic supervisory relationships requires a cultural shift within academia. This involves:

- Moving Beyond Power Dynamics: Actively working to mitigate the negative effects of inherent power imbalances and fostering relationships based on mutual respect and academic partnership.

- Recognising and Rewarding Good Supervision: Incorporating quality of supervision and mentorship into criteria for academic promotion and recognition, signalling its institutional value.

- Holding Supervisors Accountable: Consistently addressing and taking appropriate action in cases of substantiated poor supervisory conduct or ethics violations.

- Encouraging Open Discussion: Creating an environment where discussions about supervision (both positive and negative aspects) are normalised and encouraged, rather than being a taboo subject. As Gorup and Laufer (2020) advocate, this requires a "rethinking how we characterise the doctorate," moving away from the "trial by fire" mentality.

E. Implementing Feedback Mechanisms for Supervision Quality

To drive continuous improvement, institutions should implement regular and confidential feedback mechanisms for assessing the quality of supervision. This could involve:

- Anonymous Student Surveys: Regular surveys allowing students to provide feedback on their supervisory experience without fear of identification.

- Exit Interviews/Surveys: Collecting feedback from students upon completion or discontinuation of their PhD.

- Use of Feedback for Development: Ensuring that feedback is used constructively for the professional development of supervisors and to identify broader systemic issues or training needs within departments or the institution as a whole. EGU Blogs (2021) suggest implementing "a neutral and standardised way for students to provide feedback to their supervisors."

By taking these systemic steps, institutions can create an academic ecosystem that not only supports PhD students more effectively but also enhances the overall quality and integrity of doctoral education.

Key Points: Institutional Role in Healthy Supervision

- Mandatory Supervisor Training: Comprehensive programs focusing on mentorship, communication, conflict resolution, and student well-being are essential.

- Clear Policies: Accessible and fair procedures for supervision standards, conflict resolution, grievances, and changing supervisors are necessary.

- Robust Support Structures: Well-resourced Ombuds offices, confidential counselling, and dedicated graduate school support are vital.

- Cultural Shift: Promoting respect, accountability, and valuing mentorship over purely power-based dynamics.

- Feedback Mechanisms: Regular, confidential student feedback is crucial for quality assurance and supervisor development.

Conclusion and Key Takeaways

Navigating a problematic supervisor-PhD student relationship is undoubtedly one of the most challenging experiences a doctoral candidate can face. The journey through identifying issues, understanding their roots, strategising, and taking action requires courage, resilience, and a clear understanding of one's rights and available resources. While each situation is unique, several guiding principles can empower students to manage these difficulties more effectively.

Summary of Guiding Principles for Students:

- Proactive and Clear Communication: Where feasible and safe, attempt direct, assertive, and constructive communication with your supervisor as an early step. Clearly articulate your concerns, experiences, and desired changes.

- Systematic Documentation: If problems are significant or persist, maintain a factual, dated log of incidents, communications, and their impact. This is crucial for your clarity, and if formal steps become necessary.

- Know and Utilise Support Systems: Familiarise yourself with your university's policies (grievance, code of conduct, supervision guidelines) and the resources available (Ombudsperson, counselling, graduate school advisors, student union).

- Prioritise Well-being: Actively engage in self-care strategies, build a strong support network, and seek professional help if needed. Your mental and physical health are paramount.

- You Are Not Alone: Problematic supervisory relationships are a recognised issue in academia. It is okay to seek help and advocate for a supportive research environment. Many resources and individuals are there to assist.

Final Encouragement

Facing and addressing issues with a PhD supervisor demands considerable strength. Remember that you have a right to a respectful, supportive, and intellectually stimulating research environment. While the path to resolution may be complex, it is navigable. By arming yourself with information, seeking appropriate support, and acting strategically, you can work towards improving your situation, protecting your well-being, and successfully completing your doctoral degree. Your research and your contributions are valuable, and fostering an environment where you can thrive is a responsibility shared by the entire academic community.